As with Rene Magritte's famously cheeky painting about the difference between symbols and what they symbolize, the Necronomicon became a sort of hall of mirrors in the 1970s, with various publishers rushing to capitalize on the public's unstoppable desire for "the real book," despite the fact that no such book existed.

Nonetheless, the concept of the Necronomicon is now deeply imbedded in the culture. Jon Stewart makes jokes about it, the Evil Dead trilogy of comedy/horror films (Evil Dead, Evil Dead 2, & Army Of Darkness) made liberal use of it as a device, and Lovecraft himself finally has respectable looking Penguin editions of his work. How did this happen?

Let's turn back the clock a moment, in contrast to the "Simon Necronomicon" (which has almost nothing to do with Lovecraft and is essentially an eerie rehash of Sumerian mythology molded into the context of a modern "witches' spellbook") 1978 saw the release of another Necronomicon, this one edited by George Hay (creator of the Science Fiction Foundation) and co-written by philosopher and occultist Colin Wilson (author of The Outsider). This other Necronomicon actually attempted to recreate something like book to which Lovecraft referred in his stories, and included the few passages he actually "quoted," such as the famous couplet from The Nameless City (1921):

"That is not dead which can eternal lie

and after strange aeons even death may die"

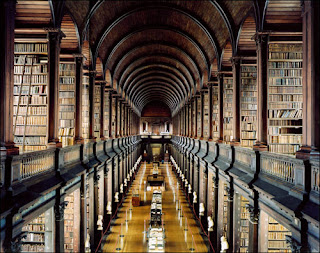

Lovecraft's fiction exudes an atmosphere of forbidden knowledge, extracted and examined by a scientific and rationalist apparatus that cannot fully comprehend its terrible scope.

Hay and Wilson, understanding this fully, gleefully slathered on an appropriately purple "back-story" to their Necronomicon: It was supposedly a computer-assisted cipher-translation of a hand-made copy of the infernal text itself, made in the late 1500s by none other than John Dee, astronomer, spy, mathematician, occultist and tutor/astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I.

Hay and Wilson, understanding this fully, gleefully slathered on an appropriately purple "back-story" to their Necronomicon: It was supposedly a computer-assisted cipher-translation of a hand-made copy of the infernal text itself, made in the late 1500s by none other than John Dee, astronomer, spy, mathematician, occultist and tutor/astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I.

All this makes for delightfully frightening fiction, because as the Blair Witch Project (1999) and the Paranormal Activity (2007- now) series have illustrated for the world of cinema, the stylistic trappings of factual reportage make for intensely powerful storytelling. In the case of cinema, this means the home video camera or security camera, which suggests realism to viewers by virtue of its low fidelity. In terms of Hay and Wilson's Necronomicon, it is the non-fiction essay style of an academic historian or art-historian that lends credence to their fictional back-story.

In fact, the "unmentionable Necronomicon of the mad arab Abdul Al-Hazred" (as he calls it in The Festival, 1923) exercised such a powerful effect on his readers that requests trickled in during Lovecraft's lifetime to produce the noxious text itself. The man himself was characteristically insightful on the subject:

"As for bringing the Necronomicon into objective existence–I wish indeed I had the time and imagination to assist in such a project...but I'm afraid it's a rather large order–especially since the dreaded volume is supposed to run something like a thousand pages! I have 'quoted' from pages as high as 770 or thereabouts. Moreover, one can never produce anything even a tenth as terrible and impressive as one can awesomely hint about. If anyone were to try to write the Necronomicon, it would disappoint all those who have shuddered at cryptic references to it."

–H.P. Lovecraft, from a letter addressed to James Blish and William Miller, Jr.

But Lovecraft's own rational materialism didn't stop famous occultist Kenneth Grant, longtime head of the highly influential Typhonian Ordo Templi Orientis (and to many people, the true inheritor of his former teacher Aleister Crowley's legacy) from blurring the fact and fiction of the Necronomicon's identity even further.

Grant (who died earlier this year) contributed to the snake eating its own tail that is the fact and fiction of the Necronomicon by suggesting that the reason for Necronomicon's enduring popularity is that it actually exists, though not in the form of any actual book. Grant claimed to have accessed fragments of the book in trance states designed to draw information from the "Akashic Records" a sort of psychic collective unconscious that certain mystics believe act as a repository for knowledge amassed by the human race over its millennia on earth. He believed that Lovecraft, who suffered from severe and bizarrely detailed nightmares throughout his lifetime, was a natural astral traveller who did not "invent" the Necronomicon, nor the horrific entities (the Outer Gods, the Old Ones, etc.) so much as stumble across them in the gnosis of lucid dream, and write about his experiences after.

Grant's claim is a twisted mirror image of the post-modernist's art-historian's point of view; that the Necronomicon exerts cultural influence because it is a powerfully crafted symbol of an archetype deeply bedded in the human mind: the tome of forbidden and unhallowed knowledge, the anti-bible, a repository of knowledge that imperils the souls of anyone who reads it.

But Grant takes a step beyond the strict Newtonian causality most academic (and thus atheistic or agnostic) cultural theorists espouse. He asserts that mental reality is reality itself, and that the Necronomicon's cultural power as a symbol makes it an objectively real phenomenon, which can be accessed via certain gnostic techniques.

As in a hall of mirrors, or any other "observer-specific reality," (to borrow a phrase from particle physics) what is actually "there" depends on what sort of phenomena you decide to call "real."

And, as Lovecraft himself might add, how you choose to describe it.

"first there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there is"

-Zen aphorism